Summary

Key questions

- What does Multi-Level Governance mean?

- Is Multi-Level Governance a key factor in making energy efficiency measures more effective?

- How to organize and manage it?

Multi-Level Governance refers to who makes decisions and how decisions are made by actors operating at multiple levels and scales (Ashwin Ravikumar, 2015)

Lead authors: Stefano Faberi (ISINNOVA)

Reviewers: Giulia Iorio and Alessandro Federici (ENEA)

Background and rationale

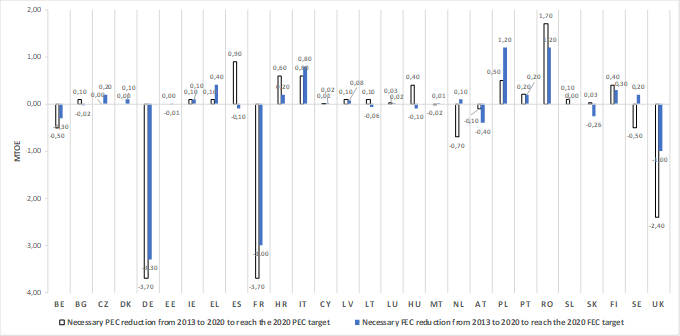

End-use energy efficiency is widely accepted as providing least-cost solutions to climate, energy security and economic goals. Unfortunately, maximizing this potential resource is proving difficult. Even if the EU Member States have already achieved or are achieving (with some exceptions) a level of energy consumption which ”equals or is below their indicative national 2020 targets, they would need to make an effort to keep this level or to further decrease it” (EU Commission 2015a, see Figure 1). This applies even more when thinking ahead to the new challenging 2030 targets foreseen by the forthcoming revision of the Energy Efficiency Directive (EU Commission 2016c). There may also be a change in the factors that favoured energy consumption reduction over the last decade: slow economic growth following the financial crisis of 2018 and higher average winter temperatures.

To achieve these targets, EU countries will have to adopt strong energy efficiency measures and make sure that the end users to which they are addressed effectively apply them. According to the opinion of several experts (EU Commission 2015b, Smith 2007, Alber and Kern, 2008), a good way to increase the effectiveness of measures is the setting of coordinated actions between multiple levels of government – international, national, regional and local.

Figure 1: Necessary annual primary energy consumption (PEC) and final energy consumption (FEC) reduction from 2013 to 2020 to reach the 2020 targets

Source: EU Commission 2015a

This type of cooperation between different national and local authorities should allow, when properly implemented, policy makers at all levels of government to

- Improve their capability to design robust and effective programmes,

- Modify under-performing programmes,

- Connect and share experience with policy makers of the same and/or different level of government.

Energy efficiency is an integral part of a broad and complex socio-economic energy system. As such, “an effective energy efficiency policy” must be designed and implemented in a way that engages the whole system of actors that influence energy productivity patterns. Key actors, in this regard, include both government and non-governmental agents” (IEA 2009). Many studies have been focused on how different levels of government can directly engage non-governmental actors (such as industry, households or transport operators) to improve their energy efficiency, but relatively little effort has been devoted to understanding how this engagement might be made more effective by coordinating the efforts of these government levels. Each of these levels play an important role in the energy efficiency implementation process, and if they act in isolation the energy efficiency potentials may not be achieved.

National governments set priorities, develop and coordinate strategies and have the capacity to mobilize significant resources. Nonetheless, they do not have direct and effective interactions with local communities and are then often obliged to delegate important aspects of energy efficiency policies to lower levels of government levels. Regional and local authorities then often act as implementation agents taking advantage of their extensive knowledge of the requirements and problems of the territory they administer. However, in turn, regional and local governments depend on the national level as regards the coordination with high level strategies, the legal framework and funding availability.

Defining and framing the Multi-Level Governance

To better understand what the term Multi-Level Governance (MLG) means, it is useful to first define the governance concept, at least in the context of this short paper. To this end we refer to the definition provided by a study carried out by IEA on the impact of MLG on energy efficiency interventions (IEA 2009). In this study, IEA defines the governance concept according to three different levels or approaches:

- “The need to focus on understanding the system of governing (Bulkeley, 2005) in all its complexity – rather than just as a traditional hierarchical, linear form of control from national to regional and local levels”

- “The understanding of the role of different actors in the governing process when national actors are not necessarily the only or most significant participants.”

- The understanding of the way these actors interact according to the “world of overlapping and competing authorities at different scales”

From these definitions, it follows that MLG “can be understood as the complex system of interactions between actors at all levels of government, engaged in the exercise of authority” (OCSE 2009). MLG can then be seen as a “…decision-making processes that engage various independent but interdependent stakeholders” (EC 2015b).

The ways to manage this decision-making process are in any case very diverse. To this end, the IEA study proposes a convincing scheme, taken from the specialised literature (Bulkeley and Kern, 2006), to frame the different governance modes into four categories: governing by authority, governing by provision, governing through enabling and self-governing.

Governing by authority refers to the typical command and control process in which national governments use mandatory legislative instruments to, for example, impose standards.

Governing by provision occurs, when national governments propose incentives and/or additional services (i.e. auditing services, consultancy, ICT facilities, etc.) in return for local action.

Governing through enabling refers to situations where national governments foster local actions by facilitating the development of such actions. This can include the provision of guidelines for local authorities or the dissemination of information and best practices. An important enabling activity could be, for example, the support for the setting up of participatory activities (i.e. the formation of multilevel discussion boards) or even laws and regulations allowing for active involvement of the stakeholders (i.e. voluntary commitments).

Finally, self-governing is characterised by autonomous local initiatives enacted to reinforce or tailor to specific local requirements, the national climate or energy efficiency legislation. It could also include creating new measures where the national legislation is limited or missing.

It is then clear that the scope and mechanisms of MLG vary a lot according to the leading governance mode. In the first case, that is governing by authority, it shall be important to reach the consensus of the parties to which the measures are addressed. In the second and third cases it is very important to reach agreement on the way the subsidies or incentives and/or the enabling activities might be effectively implemented at local level. In the fourth case, it is crucial to frame the local actions within the national context and, in cooperation with the national government, to compare them with other urban or regional best practices in order to look for possible synergies or economies of scale.

How to organize and manage a successful MLG?

There are few but important factors that have to be taken in due consideration to launch and manage a successful MLG. A document issued by the EC (EC 2015b), based on the analysis of ten case studies, highlights the following four key factors:

• Who should drive or initiate MLG processes?

There is no single designated stakeholder to initiate or drive governance processes. Very often the initiative is taken by politicians or civil servants at any administrative level. Private organizations, NGOs, universities and individuals with good networks and a broad understanding of governance can also start the process.

• Which stakeholders should be involved?

There must be a good balance, in terms of number of participants and representativeness, between the politicians and civil servants pertaining to the different administrative levels and any other stakeholders whose decision-making power or political and social influence are needed to contribute to solving the issue at stake. It is important that from the very beginning, a careful mapping is undertaken to determine the most influential stakeholders in the field.

• How to facilitate MLG processes?

To facilitate the cooperation and exchange of opinions among a considerable number of stakeholders and, possibly achieve a shared vision and consensus on the policy objectives, it is important to adopt effective communication techniques. The objective should be to create commitment and proactive participation among the stakeholders. In this context, a trusted neutral and experienced facilitator can make the difference, allowing the achievement of effective MLG of the issue at stake.

• Which are the ingredients for a successful MLG?

“Clear rules on the cooperation framework, clear roles for different stakeholders, and clear objectives for specific actions are all relevant to manage expectations and sustain engagement.”, as reported in the quoted EC document, are all basic ingredients to smooth and facilitate an effective MLG process.

An example of MLG good practice

Several interesting cases of projects have been collected and analysed in which MLG has been implemented to help achieve policy objectives, most of them concerning energy efficiency (IEA 2009, EC 2015b). Another such example is a project led by the author of this policy brief, in which stakeholder participation at regional and municipal level has been successfully implemented.

The Renewable Energy Systems Heating and Cooling (RES-H/C) SPREAD project (IEE 2015, see http://www.res-hc-spread.eu/en_GB/) in which stakeholder participation at regional and municipal level has been successfully implemented in the field of renewables for the heating and cooling end uses. In this framework, in each of the six participating EU countries, multi-level stakeholder participation was organized to agree on and support the plan development.

In particular in the Italian Emilia Romagna region almost 100 people were involved, coming from regional and local administrations, universities and the private sector. These participants developed a comprehensive strategy for the development of RES heating technologies composed of several policy measures. The role of this multi-level focus group was essential for the development of the regional H/C plan, as all of its members contributed to the identification of needs and priorities, to the evaluation of RES technologies and to the selection of the most effective policy measures. The combined efforts of the project’s working team and the stakeholders that participated in the focus group were welcomed by regional authorities, who decided to include the RES H/C plan in the third regional energy plan, officially issued in May 2016.

Bibliographic references

- Alber and Kern, 2008, Governing Climate Change in Cities: Modes of Urban Climate Governance in Multi-level Systems.

- Ashwin Ravikumar, 2015, Multilevel Governance and Carbon Management at the Landscape Scale - Project Guide and Methods Training Manual, Ashwin Ravikumar, Martin Kijazi, Anne M Larson, Laura Kowler, CIFOR 2015.

- Bulkeley H. and Kern K., 2006, Local government and the governing of climate change in Germany and the UK Urban Studies, 43, pp. 2237-2259.

- EU Commission 2015a: Assessment of the progress made by Member States towards the national energy efficiency targets for 2020 and towards the implementation of the Energy Efficiency Directive 2012/27/EU as required by Article 24 (3) of Energy Efficiency Directive 2012/27/EU. Report from the Commission to the EU Parliament and the Council, November 2015.

- EU Commission 2015b: Local and Regional Partners Contributing to Europe 2020, European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy, April 2015.

- EU Commission 2016c: Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2012/27/EU on energy efficiency, European Commission, COM(2016) 761 final, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52016PC0761&from=EN

- IEA 2009, Innovations in Multi-Level Governance for energy efficiency, Nigel Jollands, Emilien Gasc, Sara Bryan Pasquier, December 2009.

- Smith A., 2007, Emerging in between: The multi-level governance of renewable energy in the English regions. Energy Policy, 35, pp. 6266-6280.