Summary

Key questions

- How to effectively leverage the context-specific nature of the Third Sector for effective energy poverty alleviation measures?

- Which policy initiatives addresses the connection between social economy and social equity in energy transition?

- What emerges from the Italian landscape?

Lead authors: Alessandro Fiorini (ENEA)

Reviewers: Pilar de Arriba Segurado (IDAE)

Introduction

Third Sector (TS) and energy poverty (EP) have three main connection points. First, the statement “there is no universal definition” holds for both. Their conceptualisation involves disentangling complex phenomenon, identifying multiple determinants, and assessing uncertain impacts (Lloyd 2004, EESC 2020).

Second, the development of a coherent policy framework requires the acknowledgment of a multidimensional and transversal nature, in either case. TS activities contribute to local economic growth, as well as to the provision of goods and services of public relevance, in a “welfare mix” approach. Energy poverty crosscuts all relevant dimensions of energy and climate policy (energy efficiency deployment, renewable energy integration, demand-side management, user-centred systems, water-food-energy nexus, etc.).

Lastly, the TS could be a vehicle to facilitate the implementation of effective energy poverty alleviation solutions. Third Sector Entities (TSEs) have a thorough knowledge of:

- Needs of the targeted communities, along with the local characteristics of the energy system.

- Specific determinants of individual and household energy consumption behaviour.

- Methods of approach for potential beneficiaries and intermediaries to have direct personal contact with public authorities, market players, and service providers1 .

This policy brief deals with the articulate connections to be explored in defining EP strategies built upon the support to TSOs. Policy initiatives and pieces of legislation that account for these connections are described. The locally rooted nature of TS activities emerges as a key factor for tackling energy poverty determinants. Tools and experiences from the Italian landscape are presented.

Industrial EH could be utilised on-site to meet heat demands at lower temperature levels, to generate electricity (e.g. organic Rankine cycles), or to provide cooling.

Concepts and definitions

Third Sector. The starting point for the identification of TS and TSOs is the residual description that is usually reported. It is denominated “Third Sector” since it is not encompassed in the private business nor in the public sector.

Nevertheless, the residual description is not a definition per se, but rather the basis on which different theories have been further elaborated on, leading to distinct qualifying characteristics supporting alternative paradigms (Evers and Laville 2004, Alexander 2010, Corry 2010, Defourny and Pestoff 2014, Salamon and Sokolowski 2016).

Literature converges on identifying two main approaches in conceptualising TS.

- An American approach, which excludes activities aimed at profit generation.

- A European approach, which places emphasis on legal status.

The first one defines strict independence of TS from state and market. It is largely the result of the John Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project (Salamon 1996).

The European approach does not exclude profit-oriented economic players a priori, provided that the activities are meant to achieve general social purposes. The underlying reasoning is that in many private organisations the surplus is not constrained to only reward investors but is also distributed to other beneficiaries. This is the case of cooperatives, mutuals, associations, foundations, charities, and other legal statuses that recognise the players of the social economy sector (Bouchard and Salathé-Beaulieu 2021). The activities of these entities pursue mutual or general interests, and address social needs arising from specific population groups, even those generating returns (Evers and Laville 2004, Vidal 2010, Monzón and Chaves 2012)2 .

Compared to the American view, the European approach does not postulate strict “independence” of the TS from the state and the market. Social economy activities are rather inter-dependent and linked to others within the economic and social system3. Such connections define common spaces for “political resistance, social research, and campaigning” (Alexander 2010). This brings out another distinguishing factor: the adhesion to shared social objectives and the attitude to mobilise civil participation among people and communities, and to promote a democratic decision-making process. TS thus stands as a synonym of “social economy” or “sustainable economy” (Alexander 2010)4 .

The European Commission provides an overview of different definitions of social economy adopted by leading international organisations. The descriptions address the following common traits5:

- Prioritisation of people, as well as social and/or environmental aspects over profit.

- Re-investment of profits for collective and/or general interest purposes.

- Community-based and local roots.

- Democratic and/or participatory governance.

Despite a common conceptual foundation, the European TS pattern is heterogeneous. Different models stem from different cultural backgrounds and historical evolutions paths.

Table 1: Models of Third Sector (based on entities and tradition)

| Models of TSOs | EU Countries |

| Philanthropy | UK, IE |

| Civic commitment | SE, NO, FI |

| Subsidiarity | DE, BE, IE, NL |

| Cooperative (democracy and participation) | DK, SE |

| Cooperative (religious inspiration) | IT, BE, FR |

| Role of family | ES, PT, IT, EL |

Source: Defourny and Pestoff (2008)

Table 2: Models of Third Sector (based on prevailing definition)

| Area | Models of TSEs |

| Anglo-Saxon region | Public charity |

| Northern Europe | Non-profit |

| Nordic countries | Hybrid |

| Southern Europe | Social economy |

| Central, Eastern Europe | Civil society |

| Social enterprises | Cross-country |

Source: Adaptation from Salamon and Sokolowski (2014)

Tables 1 and 2 summarise the different TS models and reflect the variety of legal forms of entities recognised in national legislation and regulations.

Energy poverty. Energy poverty is a complex, multidimensional phenomenon usually referred to as “a condition in which households are unable to access essential energy services that underpin a decent standard of living and health” (Kashour and Jaber 2024). A recurring debate in literature is the distinction between fuel poverty and energy poverty. The term fuel poverty arises from the debate on the consequences of the energy crisesEnergy poverty. that occurred in the 1970s on the well-being of individuals. Some authors (Moore 2012, Bouzarovski and Petrova 2015) point out that preliminary investigations around phenomenon related to EP date back to 70s and 80s. The book by Brenda Boardman (Boardman 1991) is recognised as a pioneering work on describing the phenomenon. Works on fuel poverty highlight three main concurring causes (Boardman 1991, Hills 2011, Moore 2012):

- Low income.

- High energy prices.

- Poor energy performance of buildings.

The term energy poverty traditionally relates to infrastructural deficiencies in energy supply (poor extension of the electricity network, absence of natural gas pipelines, etc.) and technological underdevelopment (recourse to traditional sources, carriers, and devices for final domestic energy uses) that condition the possibility to have modern, reliable, and sustainable energy services (OECD 2020).

Fuel poverty and energy poverty address two different perspectives of the problem: affordability and accessibility. In either case, the presence and severity of the problem is shaped by territorial, cultural, social, and economic factors (Bouzarovski 2014).

Although the terms are not to be considered synonymous, they nevertheless refer to a common root: the vulnerability of individuals and households with respect to an adequate use of energy goods and services in their homes (Bouzarovski 2014, Thomson et al. 2017), including determining factors which must be understood.

For the purposes of this policy brief, the definition of energy poverty adopted is that introduced by art. 2(52) of the Energy Efficiency Directive 1791/2023: “a household’s lack of access to essential energy services, where such services provide basic levels and decent standards of living and health, including adequate heating, hot water, cooling, lighting, and energy to power appliances, in the relevant national context, existing national social policy and other relevant national policies, caused by a combination of factors, including at least non-affordability, insufficient disposable income, high energy expenditure and poor energy efficiency of homes”.

The policy framework

The European Pillar of Social Rights6 directly links the promotion of social economy, along with the empowerment and support of social economy entities, to actions aimed to alleviate energy related vulnerabilities.

Principle 20 (access to essential services) commits the EU to take actions so that “Everyone has the right to access essential services of good quality, including water, sanitation, energy, transport […].”7 This positioning was further reinforced by the four priorities of the EU Strategic Agenda 2019-20248.

On 4 March 2021, the European Commission published the European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan that set out three headline targets for 2030 about employment, training, and poverty reduction. The Action Plan acknowledges boosting the social economy to promote an economic paradigm to reduce social unbalances affecting fundamental services such as healthcare and assistance, housing, leisure, and affordable energy9.

EP emerges as a direct consequence of poor housing conditions for the disadvantaged (low-income) population. The Renovation Wave Initiative, the recast of Energy Efficiency and Energy Performance Building directives, the Commission Recommendation on EP, and the “steer and guidance” of the EU Energy Poverty Advisory Hub are framed within the actions for implementing the principles of the Social Pillar chapter10 “Living in dignity” objectives, under the “social protection and inclusion”.

Green transition from a social economy perspective The EU Social Economy Action Plan (SEAP) called for by the European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan, was issued by the European Commission on 9 December 202111. The SEAP recognizes the crucial role of TSEs in fostering the green transition “by developing sustainable practices […] for instance in the fields of circular economy, organic agriculture, renewable energy, housing, and mobility. [It] also increases the acceptability of behavioural changes which contribute to climate mitigation”.

Social economy is not a residual sector "filling in the gaps"; it includes providers of innovative services which reinforce sustainability and inclusivity, taking advantage of their local dimension. Social economy players operate at a community level, harmonizing the heterogenous interests of the different stakeholders involved in the green transition12. Supporting households by adopting energy consumption habits oriented to saving is a cornerstone for fighting energy poverty if disadvantaged people are prioritised.

Just transition from an energy policy perspective The European Green Deal extends the implications of the “just and inclusive transition” already addressed by the Clean Energy for All Europeans, and further acknowledges the local dimension of EP13. Progress towards energy and environmental targets must contribute to safeguarding fundamental socio-economic principles of equity.

The Just Transition Mechanism, established by Regulation (EU) 2021/1056, is one of the Green Deal’s tools for counteracting the possible negative social and economic effects of the sustainable transition. The Just Transition Fund (JTF), a pillar of the Just Transition Mechanism, aims to finance a EUR 17.5 billion investment over 2021-2027 for supporting the most exposed territories. According to art. 11 of Regulation (EU) 2021/1056, Member States must prepare local just transition plans covering one or more affected territories (regions or parts), in collaboration with the involved authorities”14. As part of the Fit for 55 package, the Emission Trading System has been reformed through the establishment of a separate scheme, called ETS2, for including the building and transport sector (DIR/2023/959). The Social Climate Fund was introduced by Regulation (EU) 2023/955 to counteract the potential adverse effect of the new Emission Trading System extended to buildings and Transport (ETS2).

The latest evolutions of the EU energy efficiency policy framework also provide solid normative recognition of the need to couple sustainable transition and socio-economic equity. The Energy Efficiency Directive recast (Directive 2023/1791, EED-III), which entered into force on 10 October 2023, introduces a formal definition of EP to be adopted in the EU (art.2-52). The same approach is also confirmed by the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive recast (Directive 2024/1275, EPBD-IV), which entered into force on 28 May 2024 (art. 2-24).

Besides the definition, both directives introduce a significant change by linking sub-targets of the binding objectives to alleviating energy poverty and energy vulnerability of disadvantaged subjects (e.g. EED-III: art.5-6, art.8-3 and EPBD-IV: art. 3-2b, 9-4a, 9-4b).

The Italian case: tools and experiences

Landscape. Based on data from the Italian Statistical Office (Istat), in 2021, the TS in Italy accounts for approximately 360.6 thousand entities employing 893 thousand people. TSOs are mostly located in Northern Regions (50% of the entities, 57% of the employees) and nearly all are registered as “Associations” (85%). The Social Cooperatives (4% of total TSOs) absorb most of the workforce (53% of total employees).

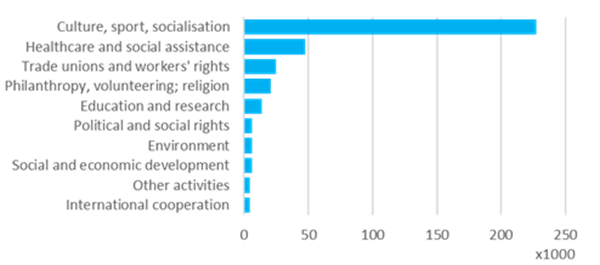

Figure 1: TSEs in Italy per sector of prevailing activity (%)

Source: Istat, Permanent Census of Third Sector Entities, 2024

Data show a prevalence of “Culture, sport, and socialisation” (227.4 thousand TSEs, 63%) and “Healthcare and social assistance” (47.5 thousand TSEs, 13%) among the designated prevailing activities. Trade unions and workers’ rights protection, and philanthropic, volunteering, religious activities jointly address an additional 13% of the total number of TSEs.

The availability of thorough information on the structure of and activities performed by the TSOs helps in designing appropriate support measures. Information on entities has been extremely improved by the Third Sector Reform that has introduced a Unique National Register (RUNTS – Registro Unico Nazionale del Terzo Settore), replacing the broad fragmentation in diverse specific registries15.

However, a detailed estimate of the building stock owned and used by TSEs is not available from official statistics. A first-of-a-kind work was carried out by ENEA in the context of the Social Energy Renovation H2020 project16.

Incentive schemes. Measures for the energy retrofitting of buildings in Italy have shown an encouraging performance in pursuing the mandatory targets set by art. 7 of the EED over the cycle 2014-2020 and art. 8 of the EED-III. In 2021 and 2022, the achievement target rate, as set out by the Italian NECP, was 100% and 98%, respectively. Preliminary data of 2023 disclose 91% coverage of the target.

The largest contribution stems from the Superbonus and the Ecobonus schemes, which account for 87.4% of the total final energy savings from fiscal deduction measures. Superbonus and Ecobonus were initially designed with specific provisions to facilitate access for economically disadvantaged people, namely the invoice discount and the credit transfer option. The first one allowed to trade the amount of the tax credit of the beneficiary directly as a discount in the invoice of the service provider. The second option enabled the sale of the tax credit to third parties (mainly financial institutions). These mechanisms were expected to facilitate access for low-income households by easing the initial capital requirements.

Additionally, specific regulations regarding maximum eligible expenditures and temporal extensions of the benefit from the Superbonus were also given by Law-Decree (L.D.) n.34 of 19 May 2020 for TSEs (art. 119, part 9-II) and social housing managers (art. 119, part 9-c). This discipline was intended to comply with the objective of maximising the social impact of public expenditure allocated to the decarbonization of the building stock.

Recently, a substantial review of the fiscal incentives for energy retrofitting of residential buildings has occurred, partly complying with the set of reforms planned in the Italian NECP17. Besides the reduction of the incentivisation percentage, significant modification of the rules for the invoice discount and credit transfer option have been made.

The Legislative Decree (LG.D.) n.11 of 16 February 2023, converted into Law n.38 of 11 April 2023, established the interruption of the possibility of exercising these options starting from 17 February 2023. The law, however, outlined exceptions, among the others for TSEs and social housing. These residual exceptions were finally removed by LG.D. n.39 of 29 March 202418. The LG.D. 39/2024 also introduced a fund of EUR 100 million for specific types of interventions carried out by non-profit organizations or similar entities (art. 1-III). and the extension to 10 years of tax deductions on Superbonus (art. 4-II).

Experiences. The Italian Energy Agency, in collaboration with different stakeholders, promotes and carries out several activities aimed at supporting the deployment of energy efficiency solutions for the TS as a mean to alleviate energy poverty. One example of these activities is the ongoing project “Social Energy Renovations (SER)”19.

The project is run by a consortium of 7 organizations, from 4 EU countries20 and aims to maximize the social impact by boosting clean energy investments in the non-profit sector and to conceive innovative services encompassing planning, technical standardization, project aggregation, social impact assessment, and credit enhancement.

SER pursues social impact results addressing energy poverty mitigation, social equity, health and wellbeing, and allowing TSEs to run their activities in comfortable and energy performing indoor spaces. Starting from Italy, replication stages are also planned for Bulgaria and France, as well as exploratory efforts in Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Poland.

One of the most relevant achievements is the establishment of the SER HUB, an integrated service provider focused on reinforcing access to affordable sustainable renovations and technical assistance for TSEs along the lines with facilitating access to secure, high impact investments aligned with ESG and impact investment criteria for investors21.

SER HUB provides support to TSEs along three categories of services:

- Financial consultancy: aimed at structuring appropriate financial solutions to support renovation projects, also collaborating with financial intermediaries, financing providers, investors, and "grant" suppliers.

- Technical assistance: for energy efficiency and retrofitting interventions (energy audits, feasibility analysis), for the creation of Energy Communities (feasibility analysis, involvement of stakeholders, etc.), for the transition to electric vehicle fleets.

- Fiscal consultancy: to support the TSEs to take advantage of incentives and available support measures.

References

Alexander C. “Third sector”, in K. Hart, Laville J., Cattani A. (eds.) The Human Economy: A citizen's guide, Part Four: Beyond market and state, 213-224, Polity Press, Cambridge, UK.

Boardman B. “Fuel Poverty: From Cold Homes to Affordable Warmth”, 1991, Belhaven Press, London, UK.

Bouchard M.J., G. Salathé-Beaulieu “Producing Statistics on Social and Solidarity Economy: The State of the Art”, UN Inter-Agency Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy, Knowledge Hug Working Paper, August 2021.

Bouzarovski S. “Energy poverty in the European Union: landscapes of vulnerability”. WIREs Energy Environment, 3(2014), 2014, 276–289.

Bouzarovski S., S. Petrova “A global perspective on domestic energy deprivation: overcoming the energy poverty-fuel poverty binary”, Energy Research & Social Science, 10(2015), 2015, 31–40.

Corry O. “Defining and Theorizing the Third Sector, in Taylor R. (eds.) Third Sector Research, Chapter 2, Springer, 2010, New York.

Creutzfeldt N., C. Gill, R. McPherson, M. Cronelis, “The Social and Local Dimensions of Governance of Energy Poverty: Adaptive Responses to State Remoteness”, Journal of Consumer Policy, 43, 2020, 635-658.

Defourny, J., V. Pestoff "Images and concepts of the Third Sector in Europe”, EMES European Network Research, WP 08/02, 2008.

Defourny, J., V. Pestoff "Toward a European conceptualization of the third sector”, in L.P. Costa, M. Andreaus (eds.) Accountability and social accounting for social and non-profit organizations: Advances in social accounting, Vol. 17, Chapter 2, 2014, Emerald, Leeds.

EESC “Creation of a European statute for associations and NGOs incorporating a precise definition of an NGO or a European association, Information Report, European Economic and Social Committee, 2020, SOC/639.

Evers A., J.-L. Laville “Defining the third sector in Europe”, Chapter 1, in (eds.) Evers A., J.-L. Laville, “The Third Sector in Europe”, 2004, Edward Elgar, Northampton (US).

Hills J.R. “Fuel poverty: the problem and its measurement”, CASE Report, 69 (October 2011), 2011, Department for Energy and Climate Change, Londra.

Kashour M., M.M. Jaber “Revisiting energy poverty measurement for the European Union”. Energy Research & Social Science, 109(2024), 103420.

Lloyd P. “The European Union and its programmes related to the third system”, Chapter 9, in (eds.) Evers A., J.-L. Laville, “The Third Sector in Europe”, 2004, Edward Elgar, Northampton (US).

Monzón J.L., R. Chaves, “The Social Economy in the European Union”, Europeaan Economic and Social Committee, 2012, Brussels.

Moore R. “Definitions of fuel poverty: Implications for policy”, Energy Policy, 49(2012), 2012, 19-26.

OECD “Greening energy and ensuring a just transition for men and women”, Issue Notes, 2020 Global Forum on Environment - Session 6.2, 2020, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Parigi.

Salamon L.M. “Defining the Nonprofit Sector: The United States”, Working Papers of the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project, no. 18, edited by L.M. Salamon and H.K. Anheier, 1996, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Institute for Policy Studies.

Salamon L.M., S.W. Sokolowski “Beyond Nonprofits: Re-conceptualizing the Third Sector”, Voluntas, 27(2016), 2016, 1515-1545.

Salamon L.M., S.W. Sokolowski, “The third sector in Europe: Towards a consensus conceptualization”, TSI Working Paper Series No. 2. Seventh Framework Programme (grant agreement 613034), 2014, European Union. Brussels: Third Sector Impact.

UN, New economics for sustainable development: Social and solidarity economy, United Nations, 29 March 2023, 2023 available at: UN, 29/03/2023

Vidal I. “Social Economy”, in Taylor R. (eds.) Third Sector Research, Chapter 2, 2010, Springer, New York.

Notes

- 1: As argued by Creutzfeld et al. (2020), “state and supra-national policies are unable to tackle energy poverty alone and that these grassroots initiatives, based at a local level and within communities, represent an important site at which energy poverty is being addressed”.

- 2: Monzón and Chaves (2012) trace the term social economy back to the introduction of studies by Charles Dunoyer in the first half of the 19th Century. Vidal (2010) attributes the introduction of the term “social economy”, at the beginning of the 20th century, to the French economist Charles Gidé.

- 3: Corry (2010) synthetizes the distinction between a separate sector, which fill the gaps left by state and market, and a hybrid social economy model, in which players cover state and market failures.

- 4: Other similar concepts are the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE) defined by the United Nations (UN 2023) or plural economy (Evers and Laville 2004) or people’s economy (Corry 2010).

- 5: See: Evers and Laville (2004) and European Commission, Social economy definitions and glossary, available at the following: Link.

- 6: The European Pillar of Social Rights was established during the EU Social Summit meetings in Gothenburg in November 2017.

- 7: See: The European Pillar of Social Rights in 20 principles, Chapter III: “Social protection and inclusion”, available at the following: Link.

- 8: See “A new strategic agenda for the EU”: 2019-2024, available at the following: Link.

- 9: See: Social Pillar. “Living in dignity/Social protection and inclusion”.

- 10: Implementing the principles of the Social Pillar. “Living in dignity” objectives, under the “social protection and inclusion” chapter

- 11: See: COM/2021/778/EU and SWD/2021/373 of 09 December 2021.

- 12: SWD/2021/982 of 09 December 2021.

- 13: See: COM/2016/860/EU of 25 February 2016 and COM/2019/640/EU of 11 December 2019.

- 14: Based on the common template set out in Annex II.

- 15: Legislative package, implementing the framework set out by the Delegation Law n.106 of 6 June 2016.

- 16: Forthcoming deliverable. See: Link. The SER Project received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant Agreement No 101024254.

- 17: See Italian NECP (PNIEC), June 2024, Section 3.2.

- 18: Converted into Law n.67 of 23 May 2024.

- 19: For further information, see the SER Project website.

- 20: GNE Finance (ES), ENEA (IT), Fratello Sole (IT), CGM Finance (IT), Politecnico di Milano (IT), Secours Catholique (FR), Econoler (BG).

- 21: For further information, see the SER HUB website